Recently, Calum Marsh authored an article in the New York Times titled “It’s a Visual Effects Extravaganza, but There’s Not an Explosion in Sight.” This article explores particular types of VFX effects work designed to be invisible to the viewer and the lengths of “crafting deception” in current moviemaking, using such examples as Alfonso Cuaron’s Roma and Guillermo Del Toro’s Nightmare Alley, along with CGI work done even to change actors’ performances (and that cannot be cited by name because of nondisclosure agreements). Which then begins to lead us down the thorny and barely-explored paths of AI.

In earlier posts, mediateacher.net featured conversations with award-winning VFX supervisor Greg Butler, who was one of the wizards behind a groundbreaking and powerfully breathtaking example of invisible VFX: 1917. Moreover, from the very beginning of motion picture history (which is particularly explored in Chapter 2 of Moving Images), we learn that the initial developments of using moving images to delight and entertain through deception began in significant part through the work of an actual magician, Georges Méliès.

In earlier posts, mediateacher.net featured conversations with award-winning VFX supervisor Greg Butler, who was one of the wizards behind a groundbreaking and powerfully breathtaking example of invisible VFX: 1917. Moreover, from the very beginning of motion picture history (which is particularly explored in Chapter 2 of Moving Images), we learn that the initial developments of using moving images to delight and entertain through deception began in significant part through the work of an actual magician, Georges Méliès.

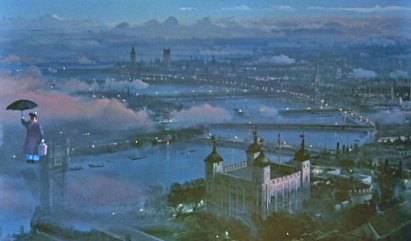

The work by Méliès and other early innovators (check out the set in G.A. Smith’s The Kiss in the Tunnel or those matte effects and dummy in The Great Train Robbery) commenced a journey in which creators of all kinds have worked to craft worlds that push the limits of what viewers can accept and believe in the worlds they experience on the screen, from backdrops to matte shots to art direction to makeup and costumes to all the myriad crafts that are used in film production and post-production.  A particular arena in which parallels can be drawn to what is described in the article by Calum Marsh is explored in such books as The Invisible Art by Mark Cotta Vaz and Craig Barron or The Art of the Hollywood Backdrop, which investigate graphic illusions created by artists in Hollywood across many years of fabricating visuals that come to life through the power of moving images.

A particular arena in which parallels can be drawn to what is described in the article by Calum Marsh is explored in such books as The Invisible Art by Mark Cotta Vaz and Craig Barron or The Art of the Hollywood Backdrop, which investigate graphic illusions created by artists in Hollywood across many years of fabricating visuals that come to life through the power of moving images.